Why would I ever want to play a video game created by AI?

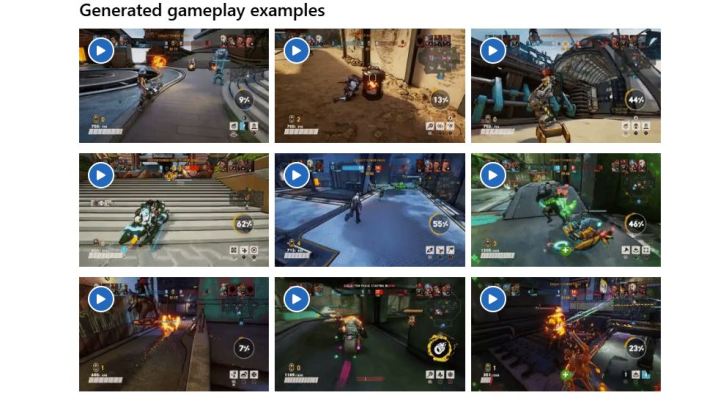

The generative AI craze has come for video games. While companies like Square Enix and Ubisoft have been casually experimenting with the tech for years, Microsoft jumped into the race this week. The company revealed its new AI model, nicknamed Muse, which it describes as “the first World and Human Action Model.” The short of it is that Microsoft collaborated with Ninja Theory to research a new generative game development model that was trained on Bleeding Edge. The end result is a model that can generate “gameplay sequences,” as shown in a series of low-res videos. Microsoft has big plans for the tool, saying that it can be used to assist developers, preserve lost games, or even create content for existing games and insert it on the fly.

As is always the case with AI, there’s a gulf between the potentially useful things Muse can do versus the aspirational talk from executives trying to hype up a big investment. The latter is great sales pitch for investors hungry to see the countless dollars that’s been poured into the tech pay off, but I’m left with one question as a player: Who on Earth beyond that small group actually wants any of this?

That question has long been the sticking point for plenty of recent tech trends, from NFTs to the ill-fated Humane AI Pin, but it’s especially pressing when it comes to video games. The growing desire to bring more generative AI into the development process comes from a total misunderstanding of what makes gaming so special. Companies like Microsoft seem to be betting big on the idea that players don’t actually care too much about the human touches that go into crafting a game. It’s a gamble that’s bound to leave overeager adopters leaving the table with empty pockets.

The human touch

Any criticism of AI’s theoretical role in game development is tricky to approach. Companies like Microsoft have chosen their words very carefully when talking about the tech, always stressing that generative models would act in support of real people, not replace them. At last year’s Game Developers Conference, I tried out a demo built with Nvidia Ace that had me naturally talking to responsive NPCs. Nvidia introduced me to a few writers who helped create the demo, who stressed that all of the generated responses I saw were the product of their own work. They explained that they wrote extensive character biographies and fed them into the AI model, which shaped the characters around that writing. The recurring argument from companies embracing AI is that it will be used in this way, giving creators a new tool akin to Photoshop.

You can take that at face value, but the line of thinking begs skepticism. Last year, Microsoft laid off over 1,500 workers from its gaming division. The move even saw it shuttering studios like Tango Gameworks entirely, one year after it released the critically acclaimed Hi-Fi Rush. Now, we’ve learned that Microsoft was quietly training a new AI model amid those layoffs that it hopes will be capable of game development, in some form, one day. Those events were likely unrelated, but it doesn’t take a mathematician to see where the two points could inevitably intersect.

It’s time to stop playing stupid: Generative AI will replace jobs. Anyone saying otherwise is lying to you. When overpromising what Muse could do, Microsoft’s executives are not describing additive tasks that no one else is currently doing. It is someone’s job to generate worlds, preserve old games, and create content for existing ones. Why build a machine capable of doing those tasks just to make a glorified assistant? The only person in games who is being honest about the endgame is Split Fiction director Josef Fares, who recently told VGC that the tech will likely come with layoffs.

“We need to adapt to it,” Fares told VGC when asked about generative AI’s role in game development. “If it’s part of the industry we should see how to implement it to see how we get better games. I can understand the fact that some people could lose their jobs but that goes for every new technology.”

To realistically discuss the future of generative AI in video games, we must reject damage controlling assurances from executives and accept that models like Muse could indeed remove some human hands from the process. That doesn’t mean that all games will be entirely built by AI models going forward, but it does mean that you’ll see more instances where anything from a piece of art to an entire NPC conversation might be credited to an AI tool. Were Muse to reach its full potential beyond generating rough gameplay snippets, you might even wind up walking around a level entirely sculpted by AI or playing a machine’s approximation of a classic game — at least if higher ups who don’t quite understand the realistic applications of the tech have their way.

If you love video games, that reality should make your stomach churn.

There’s a fundamental flaw in the entire AI game development boom. Its loudest advocates seem to believe that players will simply play anything. If you stick a machine-imagined Bleeding Edge clone in front of their face, they will gobble it up the exact same way they would a meticulously designed passion project from a celebrated studio with something to say. There is no mental separation between those two ideas for some because we’re currently living in an age where “content” has replaced art. It’s the same thinking that has turned Netflix into a cesspool of reality shows and hastily assembled true crime documentaries. Why overthink it? A game is just a game, right?

It’s that surface level thought that is bound to backfire for those who look to AI as a cost-cutting crutch rather than a tool. All of the things players love about video games come from the humans behind them. Do you love the way Kratos’ Leviathan Axe feels in God of War: Ragnarok? That’s because a group of people sat down and discussed the weight of the weapon and how the way it is swung communicates something about Kratos’ mental state. Are you enjoying Avowed’s story so far? You only get that from a team that experienced a real pandemic and organized their thoughts into a narrative that explores how authoritarianism preys on vulnerable societies. Do you like the way The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild creates such a distinct atmosphere through minimalistic piano ambiance? That didn’t pop out of a toaster.

Generative AI may be the future, but the tech is tethered to the past.

Video games are a creative medium and creativity can only come from human beings. An AI model can simulate creativity by throwing human art into a blender and spitting up some approximation of the real thing, but the final result is always devoid of meaning. It can animate Kratos swinging an axe, but it won’t be thinking of what his body language says about the lifetime of violence he’s desperately trying to hold back from his son. It can write a story about a pandemic, but it can’t actually tell you its original thoughts on what it means. It can put piano notes next to one another, but it doesn’t have a vision of Hyrule. At best, generative AI is an energy-consuming photocopier that can only spit out grainy, black and white scans of your butt cheeks.

What is the endgame of an industry built on photocopies? So, let’s say a machine could study Bleeding Edge and spit out something that looks and plays like Bleeding Edge. What exactly is the appeal of that? I understand why it’s exciting for an investor looking to reduce headcounts, but how does that benefit the actual person playing these games? Today’s gamers are already resistant towards templatized titles that try too hard to ape what’s popular in a hollow, businesslike manner. Take a walk through the graveyard of dead battle royale games that barely survived a year.

A machine trained on Zelda games would never have thought to generate Wind Waker. No amount of digital ideation could have birthed Balatro, because nothing like it existed in a data set. And no machine could possibly preserve either game correctly without understanding the creative decisions that guided how they were built. Virtually no video game you enjoy today would exist in a world where AI models are too ingrained into the creative process. Generative AI may be the future, but the tech is tethered to the past: It can only ever remix what came before.

Naturally, the tech will improve. I’m sure Muse will be able to spit out something more than a series of the ugliest 480p gifs you’ve ever seen in your life eventually. Optimistically, maybe it will even be implemented in the right way, finding its place as an assistive tool that can help developers implement their ideas more effectively (that is, if developers really want that at all). AI, in a broader form, has been a useful part of game development for a long time after all, with a range of great use cases to be found in everything from Final Fantasy XVI to Immortality. There is a place for the tech if it is not abused. But generative AI will never truly be a full substitute for human touch in a medium defined by it. It will only ever be able to finger paint recreations of the Mona Lisa with its six gnarled digits.