Poor sleep and addiction go hand in hand − understanding how could lead to new treatments for opioid use disorder

A good night’s sleep often sets the stage for a positive day. But for the nearly quarter of American adults struggling with mental illness, a good night’s rest is often elusive.

For patients with psychiatric conditions from addiction to mood disorders such as depression, disrupted sleep can often exacerbate symptoms and make it harder to stay on treatment.

Despite the important role circadian rhythms and sleep play in addiction, neuroscientists like me are only now beginning to understand the molecular mechanisms behind these effects.

Sleep and addictive drugs have an entangled relationship. Most addictive drugs can alter sleep-wake cycles, and sleep disorders in people using drugs are linked to addiction severity and relapse. While this poses a classic “chicken-or-egg” dilemma, it also presents an opportunity to understand how the sleep-addiction connection could unlock new treatments.

Circadian rhythms and health

At the center of the connection between sleep and mental health lies circadian rhythms: your body’s internal clock.

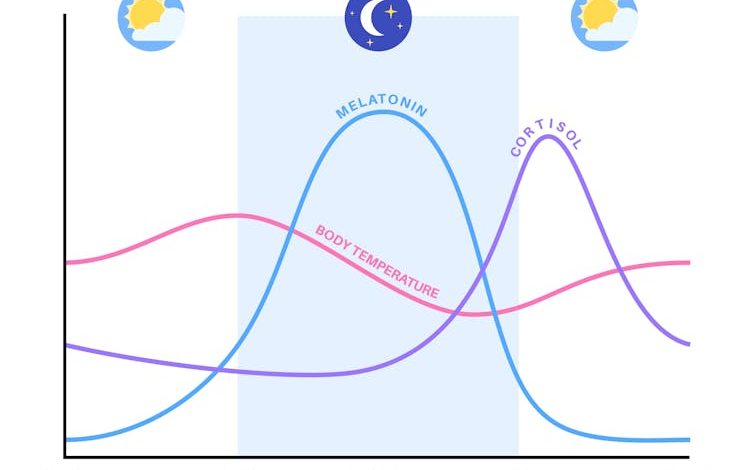

These rhythms align your bodily functions with your environment, synchronizing your body to day and night down to the molecular level. It does this through a series of proteins that interact in a feedback loop, turning genes on and off in regular patterns to support specific functions. Although your sleep-wake cycles are the most visible expression of circadian rhythms, these rhythms orchestrate most of your physiology.

Pikovit44/iStock via Getty Images Plus

If you have ever traveled across time zones, you have likely experienced a common form of circadian disruption called jet lag. This misalignment impairs your sleep and concentration, and can leave you feeling irritable.

While jet lag is a temporary nuisance, chronic circadian disruption such as frequent night shifts can lead to long-term health consequences, including an increased risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes.

Circadian rhythms, sleep and opioid use

A major focus of my lab is on opioid addiction, a disease that has claimed nearly 80,000 lives a year since 2021 in the U.S. and has limited treatment options.

People addicted to opioids often experience disruptions to circadian rhythms, such as in their sleep and their levels of corticotropin, a key hormone that regulates stress. These disruptions are associated with many negative health consequences. In the short term, these disruptions can impair cognitive functions such as attention and increase negative emotions. Over time this can worsen mental and physical health. Studies of opioid addiction in mice reveal similar disruptions in sleep and various hormonal rhythms.

Importantly, poor sleep is common throughout a person’s experience with opioid use disorder, from actively using to withdrawal from opioids, and even while on treatment. This complication can have profound consequences. Studies have linked sleep disruption to a 2.5-fold increased risk of relapse among those undergoing treatment.

Unlocking the clock for opioid addiction

Using brain tissue from deceased donors and experiments in mice, my team is identifying molecular changes associated with psychiatric disorders in people. We model these changes in mice to explore how they affect disease severity and behavior.

Through genetic sequencing and computer modeling, my lab is able to profile all the RNA molecules in a brain region and understand how their rhythmicity – the peaks and troughs of their activity across the day – changes due to opioids. This provides a complete snapshot of which genes change at what time, allowing my team to peer into the molecular mechanics that may drive opioid addiction.

Robert Reader/Moment via Getty Images

For example, we looked at two brain regions strongly associated with addiction: the nucleus accumbens and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. We found that patients with opioid addiction had completely different gene expression patterns in these brain regions compared with those without addiction. Some genes had adopted a completely different rhythm of activity, while others had lost their rhythmicity altogether.

Genes that lost rhythmicity included those involved in various components of the molecular clock and those linked to sleep duration. This further highlights how circadian disruption is a symptom of opioid use while beginning to uncover its underlying mechanisms.

In work that is pending peer review, my team focused on one major gene that lost rhythmicity in patients with opioid addiction: NPAS2. This component of the molecular clock is highly active in the nucleus accumbens and important for sleep and circadian regulation. We found that blocking functional NPAS2 formation led to increased fentanyl-seeking behavior in mice. Interestingly, we observed that female mice were willing to press a lever more times than male mice to obtain fentanyl, reflecting documented sex differences in opioid addiction among people. In another study, we also found that lack of NPAS2 exacerbated sleep disruption in mice that were administered fentanyl.

Together, our findings reinforce the role circadian rhythms play in addiction. Future work may clarify whether targeting NPAS2 could treat opioid addiction symptoms. Quality sleep isn’t just about waking up refreshed – it could also lead to reduced opioid use and fewer overdoses.